The manuscript was written at Worcester Cathedral Priory over a period of time, terminating in 1140. Compiled from earlier sources, it was revised and elaborated upon by the monk and chronicler, John. Written in the hands of at least three Worcester scribes, one of which has been identified as that of John of Worcester himself, its complex structure betrays several alterations to its content. As well as the Corpus version, six other medieval manuscript versions of John’s Chronicle are extant, representing different stages in its development, notably the ending. The manuscript, now known as MS 157, was given to Corpus in 1618 by Henry Parry (b. 1594?; CCC 1607), son of the bishop of Worcester of the same name.

As narrative illustration of chronicles only became common in the fourteenth century, illustrated historical works from the twelfth century are rare, and MS 157 is one of the earliest known examples. There are five drawings, in two recognisably different styles, indicating that two artists were responsible. The images are unique, and their particular innovation has been the subject of much analysis by art historians, whilst their contextual meaning remains relatively little studied. Recent scholarship points to a greater cohesion between text and image in MS 157 than has previously been accounted for.

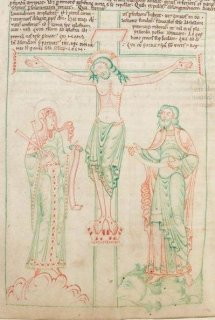

The crucifixion

Most crucifixion scenes portray the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist flanking Christ, and after the standardisation of such scenes around the middle of the twelfth century, they were depicted in recognisable, stylised postures. The two figures in the MS 157 crucifixion are not Mary and John. The woman holds two crossed sticks, and has been identified as the widow of Sarepta who fed and sheltered Elijah, who in turn revived her dead son (III Kings 17). The sticks she is holding identify her (she was gathering sticks when she met Elijah), but also prefigure the cross, and she was pictorially associated with the crucifixion throughout the twelfth century. Recent research has questioned the presence of a scroll in her hand, an attribute normally signifying a prophet, and suggested that the woman may be a Sybil. The bearded male figure standing on the oversize fish is probably that of Job on the leviathan or sea monster. The symbolic meaning is that of Christ’s victory over Satan, whilst Job’s sufferings can be seen as representative of those of Christ. Another interpretation has this figure representing Tobias, standing on the fish that attacked him whilst crossing the Tigris. The fish’s heart, liver and gall bladder were later used to drive away a demon and to cure Tobit’s father’s blindness. Even a casual observer would think of the third possibility, Jonah and the whale. With their emphasis on sacrifice, all these stories symbolise the crucifixion, and the promise of the Resurrection.

This line drawing tinted in pale red and green, which illustrates a text on the dimensions of the cross, is reminiscent of Anglo-Saxon art. Art historians have noted that it is an extremely unusual typological composition, featuring two figures whose identity continues to be the subject of some debate.

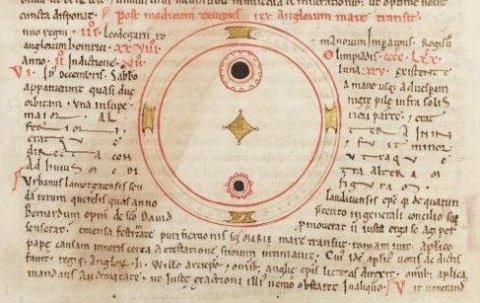

The earliest known drawing of sunspots

John of Worcester chose to illustrate as well as to describe his witnessing the appearance of two black spheres against the sun. The drawing accompanies the entry for the year 1128, and although essentially scientific in nature, it includes some decorative elements such as the png of the border.

John was obviously a keen observer of natural phenomena, as he also recorded in some astronomical detail (but did not illustrate) a solar eclipse that took place in 1130. Recent scholarship has drawn attention to the influence of Arabic science on the Chronicle. John’s references to the Arabic calendar and his use of planetary tables are proof that he had access to, and an understanding of, specialised astronomical and mathematical texts. John’s scientific knowledge was rare for his time, as was his use of tools for measuring time and space as a means of configuring the past, in order to define its relationship to the present and indeed the future.

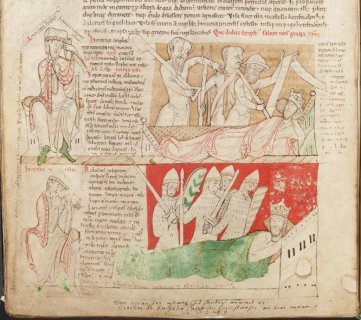

The dreams of Henry I

The visions or nightmares of Henry I are some of the best-known images from any of the Corpus manuscripts, and amongst the most frequently-requested for publication. This year, MS 157 will be on loan to the British Library, for an exhibition commemorating the Magna Carta. In his coronation charter of 1100, Henry I anticipated the Magna Carta by promising to do away with the corruption and abuses that had oppressed the people during the reign of William II. Henry ignored his own pledge, and by the 1130s, all sectors of society were disenchanted with Henry’s harsh policies and his abuse of power. The British Library curators were keen to display these images from MS 157, as they illustrate the consequences for a king of England who has failed to rule justly.

The pictures illustrating Henry’s dreams or visions appear in the section for 1131, although the text was composed retrospectively and subsequently revised around 1140-1. Judging by how tightly the text is arranged around the images, it’s likely that the drawings were completed first.

In these pages, John records that he met the royal physician Grimbald at Winchcombe, and heard from him about Henry I’s dreams. Very unusually, Grimbald appears in the first three drawings, seated on the left. He holds representative objects, and uses gestures associated with the rhetorical declamatio. Thus Grimbald becomes the narrator, a trusted witness and both visual and textual interpreter of the king’s dreams. This device lends authenticity to John of Worcester’s retelling of an episode in the king’s private life, and this visual representation of an authority figure appears to be a unique occurrence in the illumination of English historical manuscripts.

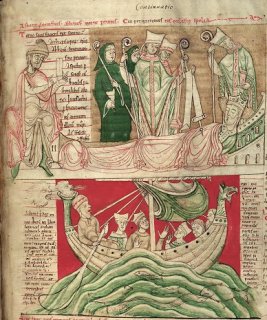

In three of the images, the sleeping king is confronted by representatives of each order of society, the rustici, milites and clerici. In the first, angry peasants present the king with a petition; this may be the first representation of ‘revolting peasants’ in western art. The second image finds Henry terrorised by four bloodthirsty knights, and in the third he is challenged by a group of bishops and monks who are enraged by his plundering of their churches. The text relates how Henry woke in dread and cried out after each dream, reaching for his weapons to defend himself. It describes his fear for his own safety in the face of his illusory attackers, and Grimbald’s proposal that Henry do penance to bring an end to his nightmares. The final image depicts the king in a stormy sea-crossing, where in fear of death he finally vows to suspend the land tax known as Danegeld (a promise later broken by King Stephen), to undertake a pilgrimage to Bury St Edmund’s, and to reinstate good government throughout the realm.

John himself does not provide a direct interpretation of the dreams, thus avoiding the trap of prophesying. In the same way, he does not state openly that an eclipse could be read as a portent or an omen, though the chronological positioning of events may intimate as much. Nevertheless, the illuminations can be read on more than one level, and the final image in the series is reminiscent of an earlier event in Henry’s life. In 1120 his son and heir William atheling was drowned at sea, along with several other young noblemen, when their vessel the White Ship capsized whilst crossing the English Channel. This personal and national tragedy caused the succession crisis that would become known as the Anarchy, but on a personal level the loss would have preyed on the king’s mind for many years to come. It would thus be unsurprising for it to resurface as a symptom of his mental and spiritual discomfort.

MS 157, among eight others previously digitised for the Early Manuscripts at Oxford University project, is now available to view at the new Digital.Bodleian platform: http://bit.ly/CorpusDB.

Julie Blyth

Assistant Librarian

Bibliography

Rosalie B. Green (1968) ‘A typological crucifixion: Corpus Christi College MS 157’, in: A. Kosegarten & P. Tigler [Eds.] Festschrift Ulrich Middeldorf, 20-23.

Judith Collard (2010) ‘Henry I’s dream in John of Worcester’s Chronicle (Oxford, Corpus Christi College, MS 157) and the illustration of twelfth–century English chronicles’. Journal of Medieval History, 36:2, 105-125

R.R. Darlington and P. McGurk [Eds.] (1995) The chronicle of John of Worcester (Oxford medieval texts)

Paul Antony Hayward (2010) The Winchcombe and Coventry chronicles: hitherto unnoticed witnesses to the work of John of Worcester

C. M. Kauffmann (1975) Romanesque manuscripts, 1066-1190 (Survey of manuscripts illuminated in the British Isles, 3), 87-88

Anne E. Lawrence-Mathers (2013) ‘John of Worcester and the science of history’. Journal of Medieval History, 39:3, 255-274

R.M. Thomson (2011) A descriptive catalogue of the medieval manuscripts of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 82-83

A.G. Watson (1984) Catalogue of dated and datable manuscripts c. 435-1600 in Oxford libraries, 126-127